Hunting has played a major role since the dawn of humanity and has often had a profound influence on society and culture. Even today, hunting is an integral part of our society.

Hunting has played an important role in human society throughout the centuries. Hunting tools such as crossbows and firearms contributed to the advancement of technology, and the passion for hunting of many rulers shaped entire landscapes. Hunting has also played a significant role in social and cultural life, and continues to do so to this day.

In the beginning there was the hunt...

Hunting is one of the oldest and most primal human activities. Even in the early days of Homo sapiens, it was a material necessity and an essential part of securing existence: the family's meat needs had to be met, and hides and furs had to be acquired as protective and warming clothing. But it also shaped the cultural and perhaps even religious development of humanity. Cave paintings indicate this.

When humans became sedentary and began to practice agriculture and livestock farming, hunting declined as a source of food. However, because herds needed to be protected from predators and fields from wild herbivores, hunting took on a new, additional purpose: to contain damage and control predators. Humans consistently pursued this struggle for millennia, leading to the extinction of large game such as fennec and elk, as well as large predators such as wolves and bears.

Hunting rights and forestry bans in the Frankish Empire

The Germanic tribes' hunting rights were initially unrestricted everywhere. After the Migration Period and with the growth of cities and settlements, extensive clearing of formerly wild lands took place, and hunting became a privilege. With the rise of Frankish power in the 8th century, kings began to reforest large forest areas, i.e., securing all ownership and usage rights to them for the crown. This legal act is known as a forest ban. The king exercised his hunting rights himself or granted them as fiefs to ecclesiastical and secular princes. The landowner, who was granted the right, also exercised hunting rights on the peasants' fields and common lands. Only in rare cases did the right of lesser hunting remain with the local population.

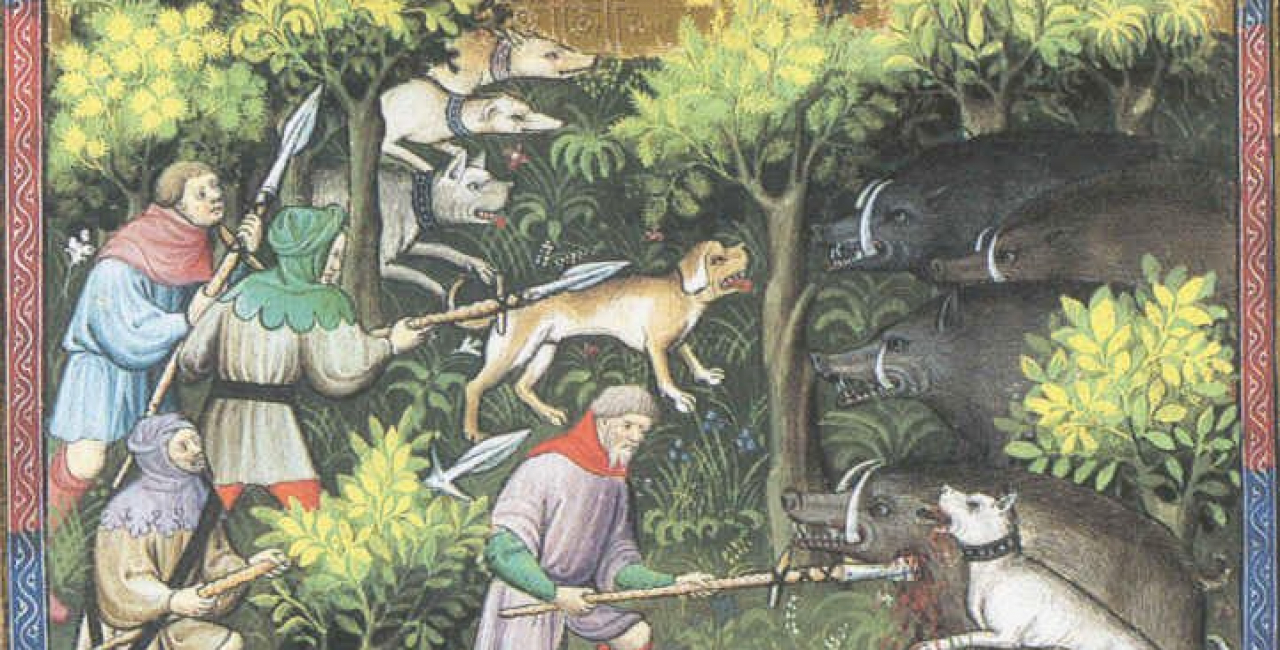

Hunting was part of medieval culture

The knights saw hunting as training for war, a sporting exercise, and physical fitness. Through it, the young men were to learn how to deal with danger and acquire strength and stamina. Hunting became an expression of court life and a favorite pastime of many rulers. The Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II, for example, wrote a very special book on the art of hunting with birds, falconry. In France, the widely traveled Gaston Phoebus wrote a comprehensive work describing the hunting of all game species and all its variations. Gaston describes, for example, horseback hunting, trapping, and how to kill wolves, those annoying competitors for prey and pests of herds, with prepared bait. He distinguished between ethical and unethical hunting. A richly illustrated copy of his work has been preserved from the library of the Duc de Berry.

Also well-known is the hunting book of the (fictional) King Modus by Henri de Ferrières (1379). It is written in a dialectical style, in the style of Greek philosophy, that is, as a questioning-explanatory dialogue between teacher and student.

We also possess a magnificently illustrated manuscript of this work from a Burgundian workshop. With the advent of the printing press, hunting books became extremely popular.

Arbitrariness of the princes and anger of the peasants

As the Middle Ages drew to a close, imperial power also declined. The dawn of the Renaissance was a time of regional princely power. Local princes considered themselves the owners of the entire land and claimed the right to hunt for themselves. Only they, as territorial princes and holders of hunting rights, could grant hunting rights on areas under their sovereignty to others. Thus, the right to hunt on foreign land arose, exercised by the lesser nobility, the clergy, and the patricians. Often, the sovereign only granted the lesser hunting rights and reserved the greater hunting rights for himself. The peasant was not allowed to hunt, but only to drive game from his fields. There was no compensation for damage caused by game. Rather, he was also required to perform feudal labor for his lord's hunting rights.

These conditions were also one of the reasons for the peasants' rebellion against the narrow constraints of the feudal and corporate state in 1525, which took place primarily in Thuringia, Franconia, and Swabia. But with the defeat in the Peasants' War, the peasants' demands also faded.

During the remainder of the 16th century, the princes' passion for hunting became a real plague (Franz, 1976). In some states, peasants were forbidden from driving game from their fields. In Saxony, they were even required to remove fences and hedges to allow game free access to their fields. Poaching was now punishable by death, as mutilation, blinding, and distemper were no longer considered sufficient to protect the noble, princely game from the common man.

First trophy cult

In the 16th century, the desire to immortalize specific hunting experiences arose by preserving mementos and attempting to document the hunt artistically in paintings and records. From then on, paintings, antlers, valuable weapons, and hunting utensils adorned the walls of castles. Hunts were developed into social events and used to represent the territorial rulers. Rituals underscored the significance of the event: welcoming tankards were handed out, and guest books were kept.

Of course, large quantities of game are needed to feed the numerous guests and to provide meat for the lavish celebrations of the multi-day events.

The desire for remembrance and to immortalize one's achievements also leads some princes to keep hunting diaries in which the exact species, quantity, and location of the prey are recorded. Landgrave Philip of Hesse is said to have sent these registers to his princely circle of friends at the end of the year to demonstrate his superiority and to annoy the lords.

"Aristocratic pastime"

But hunting had not yet reached its full decadence. This only occurred in the Baroque period. The previously common hunting style of tracking, pursuing, and killing the animal was no longer sufficient. For the sovereign and a noble social class that had largely lost its political function, hunting served only as a "noble pastime," as a book title on hunting from 1696 attests. Hunts were now organized like military personnel and planned like wars: hundreds of animals had to be mustered and presented, and ever-new perspectives and variations had to be demonstrated and tried out. The game had to be killed in a variety of ways and with great effect. A type of "water hunt" was particularly popular, in which the deer were driven into ponds or rivers and then stabbed from boats. Numerous recipes for aphrodisiacs made from the genitals, horn, or body fluids of wild animals also survive from the powder wig era.

The hunting damage to the fields, however, reaches unbearable levels for farmers during this time.

The hunt for the people!

The sovereignty of the princes was abolished with the secularization of church property and the mediatization of the German principalities at the beginning of the 19th century. Modern states emerged that strove to unify law within the new state structure.

The deposed rulers were richly compensated with land for their renunciation of sovereignty and viewed the hunting rights they still possessed on their own land, but also on the peasants' fields, as the last vestige of their former sovereignty. The hunting rights not only belonged to the nobility, they were thoroughly internalized as a symbol of noble status and a sign of lordly elevation. But they no longer suited the new era of the industrial revolution or the developing modern agriculture. This feudal hunting system had become an anachronism.

The capitalist economic system and the liberal bourgeoisie now demanded the free access to land, the legal independence of the individual, and the protection of productive property. The right to hunt on other people's land prevented, restricted, and violated these principles.

The revolution of 1848, which failed in many respects, was nevertheless a great success in reorganizing hunting rights. The Imperial Constitution adopted in 1849 stipulated that the right to hunt was tied to land ownership and that all hunting services were abolished without compensation. This was the decisive step towards bourgeois hunting. The connection between hunting and nobility, between privilege and class, was an immutable part of the estate-based society for centuries. By abolishing this connection, anyone who owned land or had the means to acquire it was able to exercise the right to hunt.

Now, however, many game species were almost locally extinct because many people took intensive advantage of their new rights. The number of hunting accidents also rose dramatically.

It quickly became apparent that exercising hunting rights only made sense above a certain size. Therefore, the hunting right, which is granted to every landowner, was separated from the right to practice hunting, which requires a certain size of property (private hunting district). Since then, properties that do not meet this minimum size have been combined into a communal hunting district.

Civil hunting is only 150 years old

A quarter of a century after the liberalization of hunting, the first interest groups for civil hunting were formed. In 1875, the General German Hunting Protection Association was founded, and two years later, a Bavarian Hunting Protection Association, under whose umbrella several regional associations operated. It wasn't until 1917 that a single "State Association of Bavarian Hunting Protection Associations" was established. During the Weimar Republic, a consolidation of the associations took place. The goal was to unite hunting, hunter, and dog clubs, as well as the game trade, gunsmiths, the arms and ammunition industry, as well as forest owners and forest officials' associations, under the hunting umbrella. This was achieved in 1928 with the founding of the Reich Hunting Association.

This aimed to standardize the still widely divergent hunting laws in the German Reich. As early as 1931, work began on a unifying hunting law, which was enacted in 1934 as the "Reich Hunting Law." The law brought unprecedented innovations to German hunting:

- Regulated management of the hoofed game populations was prescribed; terms such as game density and sex ratio, introduced for the first time, testify to this.

- The hunter’s exam became a prerequisite for hunting.

- Hunting cooperatives and hunting associations were organized uniformly.

Hunting in Germany is divided

After World War II, hunting was banned for Germans, and all hunting weapons were confiscated. Only occupying soldiers were allowed to hunt until hunting was gradually reinstated in the states and hunting laws were established that essentially adopted the contents of the Reich Hunting Law. In the Federal Republic, the right to hunt remained tied to land ownership. In the GDR, this connection was lifted, and a People's Hunting Law was introduced. Hunting management was nationalized and carried out by state-owned forestry companies. Anyone could join a hunting association and hunt for a small membership fee. However, the game killed was subject to surrender. Members of the hunting associations received monthly training, where they were introduced to topics such as hunting ethics, the preservation of traditions, hunting as nature conservation, and so on. GDR hunters were all the more horrified when the "Empire of the Privileged" came to light in 1989. Millions of state-owned marks had been squandered on the hunting and shooting passions of a few prominent individuals.

With reunification, hunting was restructured in the five new states and hunting rights were once again linked to land ownership.

Today, hunting is determined not only nationally but also internationally. The European Union is increasingly influencing hunting law and policy. Therefore, the EU's national hunting associations have organized themselves into an international association (FACE) to represent the hunting interests of approximately 7 million hunters in the European Union and the Council of Europe.

Dokumenteninfos

Autoren

Dr. Joachim Hamberger

Redaktion

Bayerische Landesanstalt für Wald und Forstwirtschaft

Alois Zollner

Bayerische Landesanstalt für Wald und Forstwirtschaft

Abt. Biodiversität, Naturschutz, Jagd

Hans-Carl-v.-Carlowitz-P. 1

D - 85354 FreisingTel: +49 8161 4591 601

Hamberger, J. (2004): Von Hirschen und Menschen..... LWF aktuell 44, S. 27-29.

Online-Version30.04.2004

(Quelle: waldwissen.net)